BY GAURI KAUSHIK ’23

Students and faculty milled around the lobby of the Mount Holyoke College Art Museum on Wednesday, Jan. 29, as poems and soft music played from a speaker. Some gathered around a table filled with snacks while others looked at the different exhibits lining the walls. Still, others wrote on sticky notes, either describing their own version of the apocalypse or sharing bits of hope on another section of the wall.

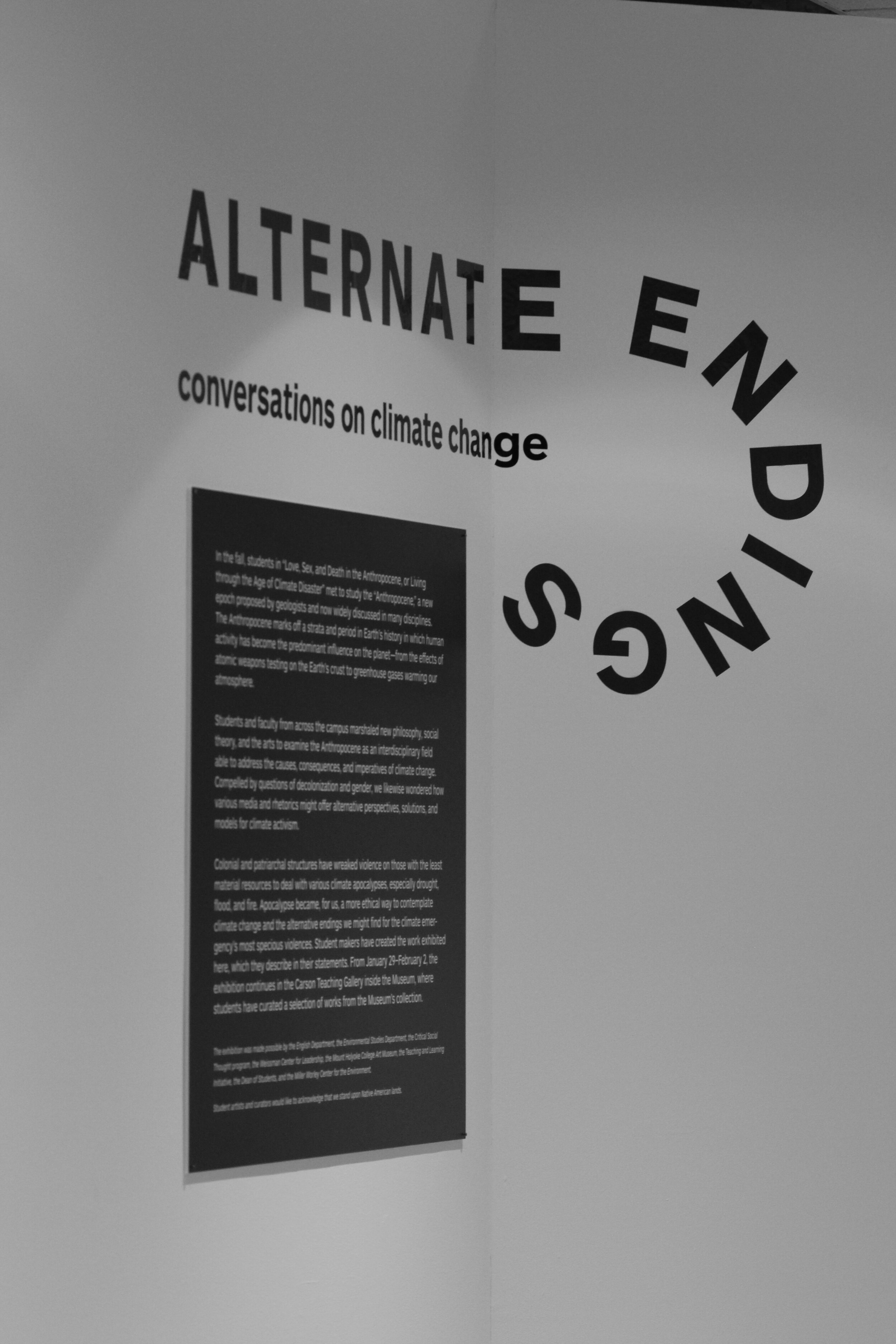

After a few minutes, Associate Professor of English and Chair of Critical Social Thought Kate Singer took to the microphone standing at the center of the hall to introduce the exhibit. Titled “Alternate Endings: Conversations on Climate Change,” the exhibit was organized by Singer’s students as their final project for the fall 2019 course, “Love, Sex and Death in the Anthropocene.”

Ana Karolina Sousa’s ’21 decision to take the course was entirely dependent on the fact that Singer was teaching it.

“She has an incredible ability to reach students where they are and bring their ideas beyond,” Sousa said of Singer. “In every course I’ve taken with her, I’ve walked in thinking I know my stance on an issue or novel and I’ve walked out with not only a new opinion, but an entirely new way of thinking.”

Maren McKenna ’20 explained the course as exploring the theory of a new geological “age of man,” or the anthropocene, centered around the concept of an apocalypse. McKenna produced a radio-style recording for the exhibit and also shared a reading. Her experience working at WMHC, the College’s student-run radio station, made it easy for her to create a compilation of others’ poems surrounding the topic of the environment and the anthropocene, along with music that went along with the piece.

“A lot of the people in the exhibit were doing visual art pieces, and there was a lot of really great visual art, but I wanted to do something that had another sensory element to it,” McKenna said.

Her piece included readings by herself and others, both in and outside of class, along with songs, focusing on showcasing indigenous and black artists.

Sousa’s contribution to the exhibit was a piece called “O Jardim,” meaning “The Garden” in Portuguese. The piece featured a silver suitcase filled with dried, waxed and gel-coated leaves and other natural debris. According to Sousa, some of the leaves were going to showcase chlorophyll-printed images of species that have gone extinct as a direct effect of human activity, but she instead sealed the images onto the leaves using a hard gel. The piece is connected to many of the readings that Singer assigned to the class. Sousa pointed out that many of the authors asked the same “humancentric” questions on climate change and race, human survival and to keep up production levels while reducing emissions.

“‘O Jardim’ is meant to ask viewers ‘just how much is capitalism worth?’” Sousa said. “My opinion ... is that climate change is real and it’s here, and it’s about much more than humans.

It’s about the countless species that have died. The trees. The oceans. It’s about restoring balance to Earth, not simply balancing human economic, political and social interests.”

Sousa and McKenna felt a sense of Photo by Rosemary Geib ’23 Featured photographs by Indira Poole ’20, titled “Deep Vulnerability” were displayed in a central cluster. Photo by Rosemary Geib ’23 Some artwork by Indira Poole ’20, titled “In-Grave-d” features pieces of plywood stacked against a wall. Photo by Rosemary Geib ’23 Indira Poole ’20 took photos of ethereal, partially covered human bodies in conjunction with nature. relief after the reception. For both, the projects and the exhibit took up a lot of time. But despite this, they felt like it was important for the community to see. McKenna found that, in many English or Critical Social Thought courses, the class delves into the theory without necessarily providing expressive opportunities, unlike the reality of “Love, Sex and Death in the Anthropocene.”

“There’s such a creative community here, so I think that it’s really great to embrace the things that people are good at, that they do in their free time and they enjoy doing and channel theory through that, because it can often be really inaccessible,” McKenna said.

For Sousa, the exhibit was important to share with the community because it covered issues like social justice, corruption, exploitation and environmental racism.

“Young people need to have conversations about the tragic and borderline irreparable status that our climate is in, and we need to foster conversations about how to restore it,” Sousa said. “This exhibit is one small step for saving the world.”