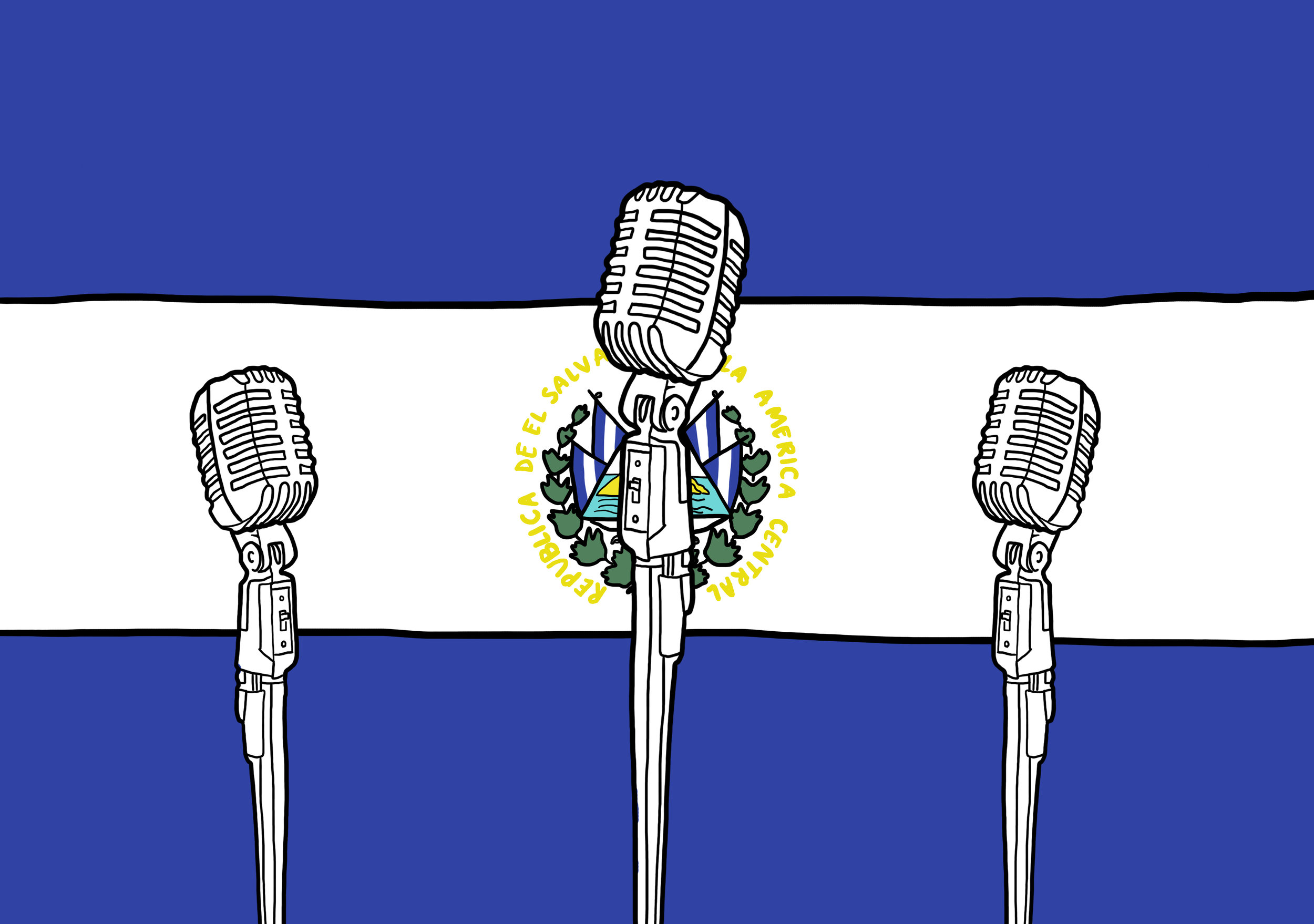

Graphic by Natalie Kulak ’21

BY EMMA COOPER ’20

Activists from El Salvador and the Pioneer Valley came together to discuss the history of violence in El Salvador and current issues facing Latin American migrants on Thursday, Sept. 13.

“Lessons from El Salvador” is part of an official UMass Feinberg Series course taught by Professor Kevin Young called “History 200: New Approaches to History,” in which students are required to attend several Feinberg lectures throughout the semester.

The 2018-2019 Feinberg Series course description defines the title of the course — “Another World is Possible” — as a mantra that reaffirmed activists’ beliefs that “alternatives to an unjust status quo were both conceivable and achievable.”

Professor Young introduced the lecture, stating, “We have asked our three speakers to share their experiences of hardship, but also the visions of a better future that have motivated them.”

According to Young, the war between the military-led and U.S.-backed Salvadoran government and the leftist guerillas began officially in 1981 and ended with the 1992 Peace Accords. He explained that although El Salvador has technically been at peace since then, it is still a site of enormous poverty and violence. “This is the context in which our three speakers live and work,” he explained, before welcoming the lecture’s first guest speaker, Carlos Henríquez Consalvi. Consalvi, known more commonly as Santiago, is the founder of Radio Venceremos, an underground radio network of the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front, a peasant insurgency group that exists today as a political party. After the war ended, he wrote several novels and short stories, including a memoir narrating his wartime experiences. Santiago also founded the Museum of the Word and the Image in San Salvador, El Salvador, and currently serves as its director.

Consalvi explained the importance of historical memory at the Museum of the Word and the Image. “We believe that in order to build a just society,” he said, “the society for which so many peasants have been fighting [...] for years and years, we have to get to know the past.” He also urged the audience members to go to El Salvador if they are able and check out the museum’s archives.

The next speaker, Rosa Rivera — who was one of the founding members of the Farm Workers Union and an organizer with the Association of Salvadoran Women during the 1970s and 1980s — echoed his sentiment. “Our community is also your home,” she said. “Please come visit... the violence the media transmits is not the whole of El Salvador.”

The third guest speaker was Diana Sierra Becerra, an organizer at the Pioneer Valley Workers Center and a postdoctoral fellow working on a collaborative project with Smith College and the National Domestic Workers Alliance. She spoke to the importance of community organizing and the effect the war has had on Salvadoran immigration to the United States, in particular the gang violence forcing people to flee the country. According to Becerra, the goal of the Workers’ Center is to “disrupt the institutions that capitalize on the exploitation of workers and immigrants.”

The majority of the event was conducted in Spanish, with near immediate translation into English. This was made possible through a complex system involving a steno machine, microphone and a team of interpreters who switched off throughout the event.

Diana Valenzuela ’20, a Latin Ameri- can studies major at Mount Holyoke, wished she could have attended the lecture. “I didn’t know about the event!” she said. “If I had known about it and it had fit with my schedule, I would have attended. It’s important to know about events occurring around the world and it sounds interesting to learn about the political atmosphere of El Salvador.” She also added, “Being a native Spanish speaker, I would have enjoyed listening to everyone speak in Spanish. I would understand their point of view, which could have been lost through English translation. I’m happy the information was accessible to both audiences.”

After a 12-year war to overthrow U.S.-backed military dictatorships and to begin their own democracy, El Salvadorians no longer want to be defined in the international imagination by the legacy of violence that has followed them since the ’80s and ’90s. The panelists highlighted the work that was done in El Salvador and the importance of community organizing to rebuilding the concept of home.