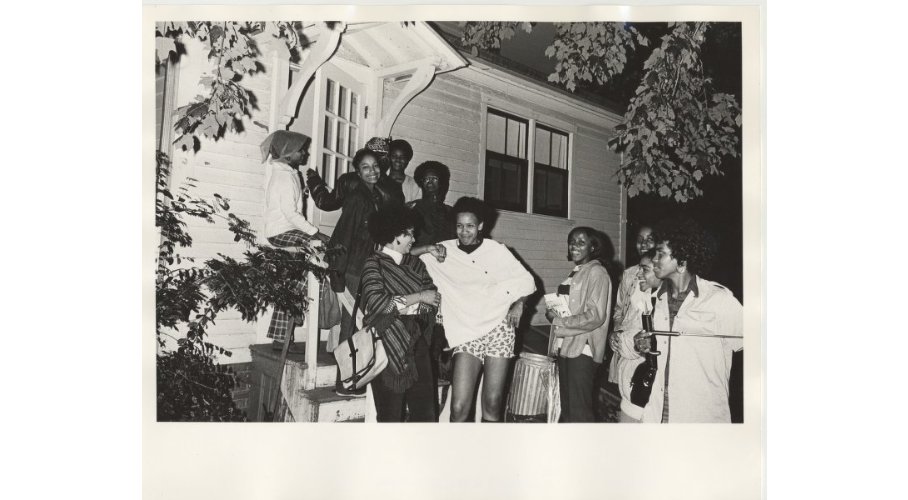

Photo courtesy of the Mount Holyoke College Archives and Special Collections

A group of students gathered outside of the Black Culture Center in an undated photo from the Archives.

BY KATE TURNER ’21

This February marks the 50th anniversary of Mount Holyoke’s Association of Pan-African Unity (APAU). Created in 1968 after multiple protests by students of color, the APAU is looking back this month at the legacy of black student activism on campus, as well as its history as an organization within the broader environment of the College.

This year’s Black History Month theme at Mount Holyoke is “I Belong Here: Celebrating 50 Years of Black Excellence.”

It was inspired by a deep sense of history, according to Tatiyana Lewis ’20, one of APAU’s Black History Month coordinators.

“First, we were focused on highlighting student activism — there was a huge boom of black student unions during the late 1960s and early 1970s,” Lewis said. “Personally, I was focused on the difference in activism on campus even between 20 years ago and now.”

According to Lewis, she and her fellow event coordinators were looking through the Mount Holyoke archives when they stumbled upon a video titled “I Belong Here” by Dominique Jackson ’04, a former APAU member.

“It just fit the need to understand our history, something even we, the e-board, didn’t have a deep understanding of,” Lewis said. “It speaks to reminding ourselves of that history, our members and the wider community.”

These ideas of history and community were heavily present in the month’s kickoff event, a lecture by Dr. John Bracey, Jr., a professor in the W.E.B. DuBois Department of Afro-American Studies at UMass Amherst. He spoke about black student activism on college campuses.

“This February, we need to ask ourselves: how can we as members continue to make space for ourselves and other students of color on campus?” Lewis said to the audience as she introduced the event.

Bracey’s lecture focused on the broad story of his own experience with blackness and activism, from the 1960s to the present day. “The reason I could do what I did is because people before me did what they did,” Bracey said. “That’s our obligation. If I pass a black person lying in a ditch or with a needle in their arm, I’m going to help them. I’m not going to walk past a black person in the gutter and say ‘that’s the way black people are.’”

“Being dumb is not black,” Bracey said. “Being smart is not white. I never, ever, ever thought there was anything black people couldn’t learn.”

More than a history lesson, Bracey’s lecture told a story, painting a picture of his life, his family and black excellence in higher education. Punctuated by snaps, applause and the sounds of assent, the audience responded positively to Bracey as he outlined the attitude of his generation, and the trajectory of activism since.

“The task of your generation — that the generation after me didn’t do — is to ensure survival,” Bracey said. “The generation after me, they thought they were going to be the richest, the prettiest, most successful. Being the best, or the richest, that won’t make you white. It makes you a rich black person. That generation of success only got you so far.”

“Can I live as a human being in this country?” he asked. “That’s not a program, that’s saying, ‘do I have the right to exist?’ ‘Do black people have a right to live?’ Your generation has brought that out very forcefully, very powerfully.”

Over the course of the lecture, Bracey continued to return to the idea of history, telling a parable of a woman stopped at the edge of the river, trying fruitlessly to get to the other side. She met a man on the water’s edge and asked him how to cross. He responded, “How does a locust get across the stream? They stack up, and one walks across their dead bodies.”

“Who is going to come with me?” the woman asked. “All of humanity,” the man replied. “And if I’m swept away?” Then, said the man, “You be the track to the water’s edge.”

“You may not see freedom in your lifetime,” Bracey told his audience. “Doesn’t mean what I did and what you do doesn’t matter. Your job is to be the track to the water’s edge.”

Bracey’s lecture was followed by the showcase of an exhibit in the Blanchard Campus Center student art gallery, featuring memorabilia from the College archives, photographs of past members and events of the APAU, and a wall of affirmations and post-it notes, where students wrote messages such as “Speak truth to power,” and “Bold, beautiful and proud!”

“Being black is being authentic, unapologetically you!” wrote Latrina Denson, Mount Holyoke’s assistant dean of students.

“As the first cultural organization established at the College, APAU embodies and honors the legacy of all students, faculty and staff from historically marginalized identities who have contributed to Mount Holyoke, the nation and the world,” said Denson in an article written on the College’s website.

“Getting to put together and plan the month ahead was a very rewarding experience, because it sort of gave me a grounding sense of my membership in this org that has really embraced me,” said Lewis.

“Even as a [prospective student], the community really took me in, told me ‘this could be your home,’” she said, “Now, looking at incoming members and the College community, I want them to see its value and love it, too.”

Lewis added, “And it’s really empowering to regain this knowledge of our history... I think that’s something really important for our body and our board, and the wider community here.”