By Casey Roepke '21 & Kate Turner '21

News Editors

“Mount Holyoke has removed a really key part of what made me feel safe — not just [as] an employee, but made me feel safe living here,” said Assistant Professor of Politics Ali Aslam, who faced uncertainty in his child care options after the College’s recent announcement that it would close the Gorse Children’s Center.

On Wednesday, Feb. 24, Mount Holyoke announced in a public statement that it would be closing Gorse within the year. The announcement has been met with organized outcry from families of the center’s students and the wider community.

The Gorse Children’s Center has a long-standing relationship with the College. According to the College’s website, the Gorse Lab School opened in 1952 in partnership with the psychology and education department. In 2008, Bright Horizons Children’s Centers LLC was selected as the management partner and entered into a contract with Mount Holyoke.

The College previously partly subsidized Gorse tuition for some College-affiliated families through the Mount Holyoke College Child Care Scholarship Program. Under this program, full- or part-time employees — faculty and staff of the College — were eligible to receive scholarship assistance if they met an “annual household income of less than $85,000” and applied for the need-based scholarship program. Discounted rates were then accessible on a sliding scale.

According to faculty parents of Gorse students, the on-campus child care offered by Gorse allows them to work without worrying about the safety of their children. “The service that is provided by Gorse is absolutely crucial for the faculty and staff at MHC to be able to do their jobs,” Associate Professor of Anthropology Elif Babül said.

Babül’s description of the services provided by Gorse — full-time day care, including infant care, after-school care, College schedule coordination and transportation for students to and from public schools in South Hadley — indicates how interwoven with the lives of faculty and staff the child care service has been. Students, too, rely on Gorse, which was previously central to the College’s psychology and education program in its capacity as a laboratory school.

The College announced the closure of Gorse on Wednesday, Feb. 24, two days after families were alerted to the change. In an online statement, it was explained that the College had formed an ad hoc committee on “employee caregiving issues” and conducted a review of the current on-campus child care options. However, according to Babül, administrators later admitted “that they [had] not considered whether there are any alternative providers in the area that can absorb the families who would be left without child care in the middle of a pandemic.”

“Essentially, it seems like the College did not consult with any stakeholders who would be directly affected by this decision,” Babül added.

Through this process, the College decided not to renew the contract with Bright Horizons and initially announced that Gorse would close on June 30, 2021, when the College’s current contract with the company expires.

The College declined to comment on any aspect of the Gorse closure decision or subsequent communication.

Backlash and extension on child care

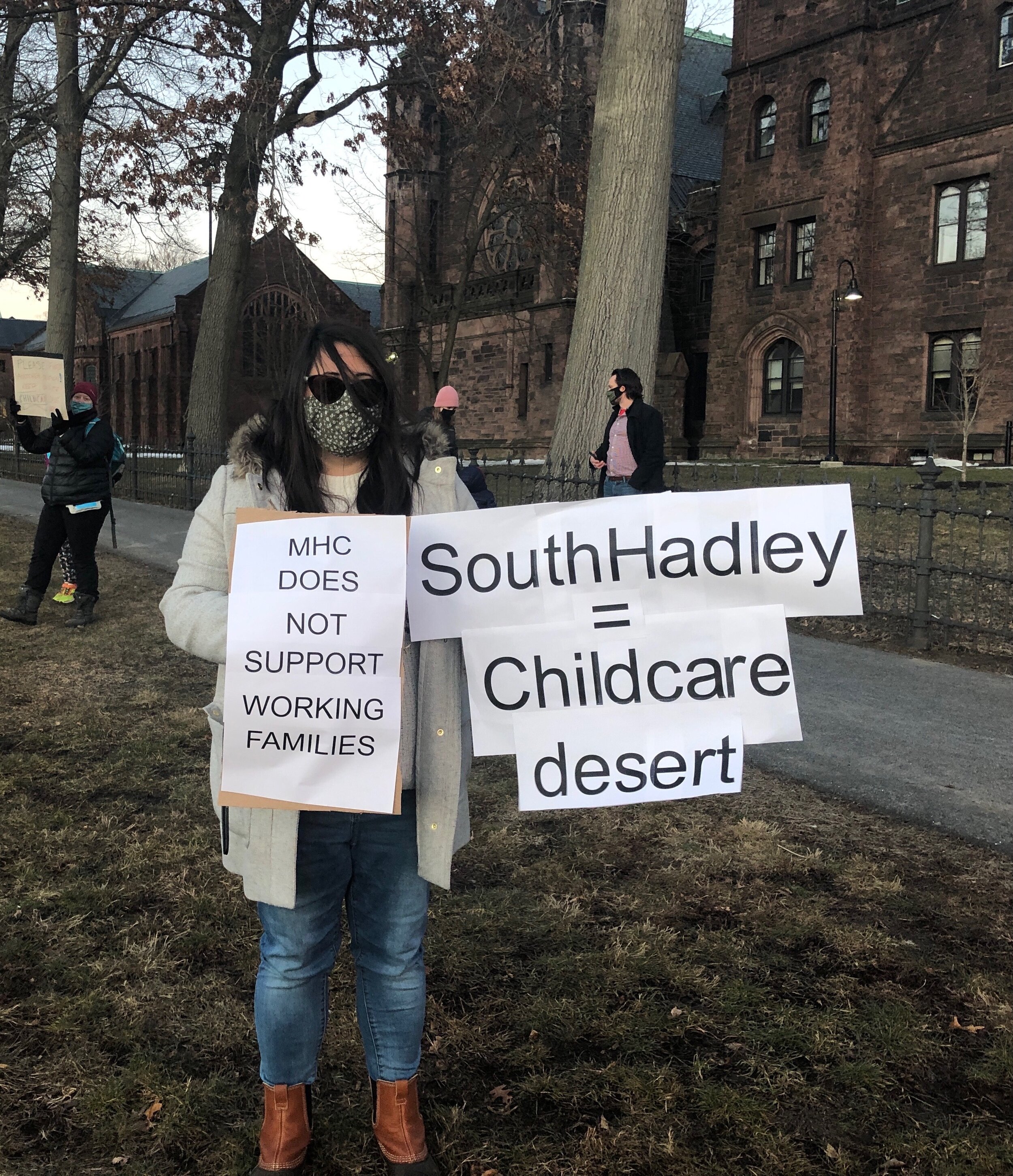

Immediately after the original announcement, a letter of protest sent by a Gorse parent gathered hundreds of signatures in 12 hours, according to the Hampshire Gazette. A petition that also circulated around the College and South Hadley community gained over 500 signatures. Faculty, staff and community members held a protest at the College gates on Thursday, Feb. 25. Families held signs painted with slogans like “Don’t evict toddlers” and “Save 24 daycare center jobs.”

Following the outcry from faculty, staff and parents of Gorse students, College President Sonya Stephens sent an email to faculty and staff on Sunday, Feb. 8, “to acknowledge and sincerely apologize for the extraordinary stress” caused by the announcement and to tentatively offer on-campus early education for the children of Mount Holyoke faculty and staff as a bridge solution to Gorse’s closure.

On Tuesday, March 2, the College followed Stephens’ email with an announcement that it had extended its contract with Bright Horizons for a single year, an “interim solution” that will keep Gorse in operation past July 1, 2021. As of March 3, the College has not publicly indicated an end date to Gorse’s operation.

Associate Professor of Art History Jessica Maier is not convinced by the College’s apology, nor by Stephens’ promises. “I believe she [Stephens] is sorry, but the problem is that she offered no real solutions in that message,” Maier said. “‘Bridge care’ is by definition temporary. Seeking feedback, meanwhile, just creates work for people who are already overworked without any clear goal — and I fear it is a stalling tactic.”

While Maier thought Stephens’ statement was a start, she highlighted the importance of continuing to advocate for permanent child care support through the College. “I will still fight hard for what it’s missing: namely, an explicit commitment to long-term, quality, financially sustainable, on-campus child care at Gorse — in the same building with the same staff — beyond next year,” she said. “That might well be with new management, but so be it. I want to make very sure that this one-year contract is not seen as a temporary bridge toward closure but rather a lifeline leading once and for all to making child care an established fixture of our campus and community. We can’t fight this fight every 10 or 20 years. I think it is part of the mission of Mount Holyoke to be a leader when it comes to supporting women and families.”

Parents, faculty and staff remain frustrated with the College’s initial decision as well as the lack of transparency concerning the process that led to the decision and the way it was communicated to Gorse families.

According to Allison Lepper, a parent of a Gorse student, “The message conveyed to the community of Gorse families was that Mount Holyoke had decided to end its partnership with Bright Horizons, and that the contract with Bright Horizons is set to expire on June 30, 2021.” This message raised a few questions for Lepper, namely “when Mount Holyoke knew negotiations had broken down such that the relationship with Bright Horizons would not be continued” and whether or not the College “had explored any alternatives for keeping the center open beyond June 30th prior to communicating its intent to close the center.”

While Lepper is unaffiliated with the College, she said that the “limited communications” she had received from Mount Holyoke “indicated that it did not believe the management fee for the center was financially sustainable, that the center served a small population of Mount Holyoke employees, and that they were concerned about ‘equity’ in continuing the center's operation.”

“We dispute these justifications,” Lepper said.

“It has become common knowledge that Gorse staff and management were not aware that the closure of Gorse was happening, or even up for discussion,” Emily Hartley-Robles, a former Gorse employee, said. “In fact, [the College] administration admitted to faculty that this information was intentionally withheld from Gorse staff and families in order to prevent them from looking for other jobs or childcare options, respectively. Withholding this information gave families and staff even less time to make alternate plans.”

“Intentionally setting up the Gorse community to have to scramble would be immoral in regular times, but to do this during a pandemic when both child care and employment options are in short supply is truly inexcusable,” Hartley-Robles said.

Long waitlists, few providers

“My child has been evicted from Gorse,” Aslam said. After the College announced the closure, Aslam and other parents were given the challenging and urgent task of finding replacement child care options.

“We all scrambled to call other providers, which is something Mount Holyoke did not do,” Aslam said. “We all discovered [that] in a pandemic, social distancing in classrooms means fewer spots available. To me, the idea that Mount Holyoke has set up an emergency fund to address equity is a reversal. It has created a greater problem of equity, because it has turned families away from a safe reliable child care option. Even if I get a subsidy … that means nothing to me if I have nowhere to spend it. Where am I going to find child care?”

Aslam isn’t the only parent to feel this way.

“My husband and I both work full time,” Lepper said. “We have contacted numerous day care centers in the area and are being told that there is a one to two year waitlist for new enrollees. Most, if not all, of the families at Gorse are currently faced with this untenable situation.”

“I have been told that a nearby child care center might have a spot for my 4-year-old beginning September 1, but there is no guarantee and in fact seems unlikely,” Maier said. “They state with certainty that the soonest they might have a spot for my 1-year-old would be fall of 2022. They have almost 60 families on their waitlist.”

Nicole Amrani is the department coordinator for the physics and astronomy departments. Her two children were enrolled in Gorse prior to the pandemic, though with the shift to remote working and learning, she has kept them at home all year. Still, she was anxious about the decision to close Gorse, even after its extension through next year. For Amrani, finding alternative child care options in South Hadley was extremely difficult even before the pandemic forced centers to limit their enrollment numbers and class sizes.

“If [the College] had done any research, just in South Hadley, they would’ve seen there are no options,” Amrani said.

While the College provided guidance to Gorse families in a Caregiver Resources document, the recommendations included links to websites for hiring a caregiver or finding remote learning groups, which are not congruent with the curriculum-based programming run through the Gorse Children’s Center.

“It’s not the ’90s,” Amrani said. “I’m not going to call 1-800-BABYSITTER. It’s just not like that.” While nannying or permanent caregivers — such as family members in the area — were options put forward by the College, Amrani was frustrated by the eventual closure of Gorse’s structured curriculum.

With long waitlists and few providers, Maier said there are only a few options for parents to pursue. Short of hiring a private nanny, which might be prohibitively expensive apart from other curricular concerns, Maier said that she or her husband would have to consider taking an unpaid leave of absence from work.

“My husband works out of state and his income is higher than mine, so logically it would be me making the career sacrifice — and yet again my kids would miss out on critical socialization and have a professionally unfulfilled mom,” she said. The other option she envisioned would be to take on additional child care duties while remaining a full-time employee.

“I [could] try to full-time parent and teach simultaneously — forget research in that scenario, there’s just no way — which will mean I will have to choose whether to do a horrible job at one or the other: being either a completely failure as a professor and scholar or a complete failure as a parent,” Maier said.

“As someone whose spouse works in an out-of-state college with a two-hour commute each way, I am practically a single parent during the week,” Babül said. “I count on Gorse to have child care that is fully coordinated with the College calendar for my two-year-old daughter and after-school care for my kindergarten-age son in order to be able to do my job.”

Because the closure has forced parents to find individual solutions, it has the added effect of separating Gorse families at a time when they are attempting to organize. “They are going to effectively scatter Mount Holyoke families, and in the process of doing so, weaken our ability to hold them even to account to this vague promise of looking into other service providers,” Aslam said.

“Gorse is where I built my community”

Gorse stood out to parents not just for its College-adjacent working hours and affordable tuition but also its pedagogical approach and commitment to cultivating community among students and families.

Aslam’s older daughter graduated out of Gorse during the pandemic, and his son is still enrolled in the program. Gorse’s closure was devastating to Aslam for its larger implications on his children’s comfort and sense of community.

“Both of [my kids] had fantastic teachers, but they have been the only children of color at Gorse,” Aslam said. “I took a great measure of security of the fact that Gorse is associated with Mount Holyoke. … The pedagogy was harmonized with the values that I take pride in and uphold at Mount Holyoke — the commitment to diversity — and I can’t get that at other places.”

Babül also valued the intention and care that Gorse teachers brought to the classroom. “In all the classes that my son has been in, the teachers made the effort to learn some words in Turkish, label the classroom items and [play] songs in my son’s mother tongue,” she said. “They recognized and celebrated Ramadan and Eid alongside other holidays. … I trusted the administration, the teachers and the parents to operate in line with the worldview that I want my children to grow up with.”

Gorse’s services also played a role in the living arrangements and locations of some Mount Holyoke families.

“As someone who started in campus housing,” Aslam continued, “Gorse is where I built my community.”

“I immensely valued their attention, care and effort to be inclusive — something that I do not feel like I can automatically count on in other child care centers,” Babül added. “I made my decision to purchase a house in South Hadley because I thought I would have a child care service I could count on.”

“The fact that they had the audacity to do this during a pandemic, when the general stress levels are already high [and] particularly acute for parents, people of color and women who have been picking up greater care responsibilities, … [and to pay] back the all-female caregivers who were furloughed for six months with no pay [only to] come back and take care of our children [by] cutting them loose in a pandemic — … this does not square with the values I thought Mount Holyoke was committed to,” Aslam said.

“Studies show that the significant adverse effects of having children on research productivity is doubled for women,” Babül said. “Women are also overwhelmingly bearing the effects of increased child care burden due to the pandemic. For all the progressive values that Mount Holyoke professes to adhere by, provision of on-campus child care should be an unwavering long-term commitment.”

An equity decision?

In the College’s online College Advisory statement, the decision to close Gorse was presented as a remedy to inequity.

“[Currently the] few employee families who choose [the] Gorse Children’s Center receive a disproportionately large subsidy and families that choose other providers for affordability or other reasons receive no College-sponsored financial support for childcare,” the statement said. “This inequity in the distribution of resources allocated to subsidizing child care simply cannot continue.”

Administrators including Stephens have reiterated several times that only 10 Mount Holyoke families currently enroll children at Gorse, a statistic Babül and other faculty members say is “completely misleading,” as it only takes into account Gorse’s pandemic enrollment numbers.

“Many families had to take their children out of day care during the pandemic for safety reasons,” Babül explained. “The center had to operate in half capacity as per state regulations. Also, many of the services other than full-time preschool care … were suspended, therefore excluding from the picture families who regularly used those pre-pandemic.”

These considerations suggest that the number of Mount Holyoke-affiliated families who normally enroll or have enrolled children in Gorse may be higher than administrators have indicated. When questioned about enrollment numbers, a College spokesperson was not available for comment.

While the College has not commented on the exact group responsible for this decision, the Financial Review Group was consulted in an advisory capacity. Maya Sopory ’22 currently serves as the president of the Student Government Association, and, along with Juniper Glass-Klaiber ’21 and Maha Mapara ’21, is one of three students serving on the Financial Review Group, one of the College’s Coronavirus Emergency Response Teams. Sopory said that as an advisory committee, the FRG was not involved in any voting process, but heard a presentation on the financial topics surrounding Gorse, and FRG members were invited to provide feedback and discuss the issue.

“This decision exemplifies to me that individual student representation is not enough,” Sopory said. “While it is important, the reality is that inclusion is the first step of many. A genuine shared governance institution is much more than bringing in three students to represent the immense array of experiences, especially those with marginalized identities, of over 1,500 students. To me, this decision is endemic to Mount Holyoke’s governance system and a symptom of a larger problem.”

Sopory also emphasized that while this decision was problematic for its impact on Gorse families, the effects would be even more widely distributed.

“The closure of Gorse hurts all members of the community,” Sopory said. “Students for years have demanded that the College hire more faculty members of color. Gorse is a significant incentive to potential incoming faculty, and its closure would take away a space for safe and comfortable integration into the Mount Holyoke community.”

Sopory added that the increased burden of child care, in addition to placing faculty in a difficult position, will worsen the effects of the pandemic on students’ learning, too. “Parents without a safe place to send their children will be less available to students [for] office [and] drop-in hours, [have less] meeting availability [and have less time to] create resources, and the increased stress of child care will stretch working parents even further,” Sopory said.

Psychology and education program

Beyond the more general effects on faculty engagement, students in Mount Holyoke’s psychology and education department are anxious about what the closure means for their curriculum.

“I genuinely had to take a moment after the news to wonder if I should transfer or not,” said Camy Mayo ’22, a psychology major. “One of the main reasons I applied to Mount Holyoke was because it had access to a developmental center like Gorse — a good developmental center.”

In its original announcement, the College stressed that “the relationship with [the] Gorse Children’s Center is no longer integral to the curricular needs of the Psychology and Education Department.”

“This is an accurate statement,” said Katherine Binder, chair of psychology and education and professor of psychology. Binder explained that Gorse was “just one of many potential sites” for student placement in several lab courses.

Binder explained that part of the subsidy that the College paid to Bright Horizons supported curricular initiatives for the psychology and education department. “The Dean’s office had several conversations with me … and with the faculty who might place students at Gorse for various classes … over the past year,” Binder said. “At all of the meetings, I felt Dean [Dorothy] Mosby asked excellent questions so that she had a good understanding of how we use Gorse in our curriculum, and she discussed with us alternative options for placements. I always felt that she wanted to make sure that our curricular goals would be met, even if we did not have access to Gorse, and importantly, that students would have the experiences that were an important part of their psych/ed education.”

“We are a resourceful department and there are a number of resources in the area where our students can learn about child development in diverse settings,” Binder said. “We have been communicating with other sites this year.”

Still, students worry not only about the effect of the closure on their education, but also about the impact on Gorse students. “It kind of makes me sad thinking about how many kids I knew in the classroom had been going to Gorse since they were babies, like the employees have watched them grow up since then,” Mayo said. “There were a lot of kids I knew that had just started coming out of their shell, and I wonder how this change will affect them, you know?”

Listening session

Three days after notifying families of Gorse’s closure, the College held a listening session to field comments and concerns. Vice President for Finance and Administration and Treasurer Shannon Gurek and Vice President for College Relations Kassandra Jolley represented the administration at the event.

“[The listening session] was to allow community members to express how they felt but that also meant that those words would have no bearing on the finality of this decision,” Aslam said. “That was made clear at the start of that session. I think a lot of Mount Holyoke students understand exactly what I’m talking about.”

The listening session was also scheduled in a class slot during which professors — including Aslam — were teaching. “I just think there is no reason other than to suppress our participation and attendance,” Aslam said. “Maybe you shouldn’t schedule a listening event on such short notice for something that is so important.”

According to Aslam and confirmed by other anonymous faculty members, tensions were high at this listening session. “I think that a lot of people who attended were very upset, I know I was,” Aslam said. “The administrators present were impassive in their listening, and that also is really troubling. It was upsetting to me especially when the administrators admitted that they had done no research whatsoever to investigate the situation of families cut loose from Gorse.”

Maier was present at the listening session and felt that faculty concerns went unaddressed by the administrators. “The atmosphere [at the listening session] was marked by extreme frustration at the inability or unwillingness of the administrators present to answer our questions about such basic matters as how the decision came about, what alternatives were explored or why weren’t they explored, what data the decision was based on [and] why they couldn’t or wouldn’t cite pre-pandemic data,” Maier said.

Faculty were later dismayed to discover that this year does not mark the first instance of such conflict over child care provisions.

“During our conversations with senior colleagues, we realized that the MHC community has been consumed by the exact same crisis in the early 2000s. When we look at correspondences from that time, we see that the lines of argument are almost identical. We should find a permanent solution to what seems to be a recurring problem so that we don’t have to fight the same battle every 20 years,” Babül said.

“We need the College to decisively commit to continue providing accessible, reliable and quality on-campus child care in the long run,” she said. “As an institution that espouses women’s empowerment, Mount Holyoke should not settle for anything less.”

The College’s handling of the initial closure decision, and its subsequent apology, has raised questions from faculty over the efficacy of Mount Holyoke’s “shared governance” structure in which administrators, faculty, staff and students are supposed to share decision-making responsibilities.

After a year in which faculty retirement benefits have been cut in half and over 100 staff members have been furloughed, faculty are frustrated at what seems like an additional cost-cutting measure being framed as an equity decision. In a response to Stephens’ apology, a group of nine faculty members including Maier and Babül wrote, “After childcare, what is next? … Will we see permanent loss of retirement benefits? Salary cuts? Raised course loads?”

“This matter, which was so shortsighted and outrageous, and executed in such a ham-fisted manner, raises larger issues with trust in the governance of the College [and] its decision-making processes, not to mention its ability to foster good will with the various stakeholders — faculty, staff, students, temporary and permanent employees, alums,” Maier said. “What other decisions are next?”